Rethinking PostgreSQL buffer mapping for modern hardware architectures

Traditional database engines were designed in the '80s and early '90s. At that time CPUs were much slower than they are today. Even worse was storage, hard drive head positioning time was enormous1. And CPU (or, at most, a few single-core CPUs) was assumed to be infinitely fast in comparison to IOPS. Therefore, systems were designed to save IOPS as much as possible, while CPU overhead was considered a secondary optimization target.

Nowadays, modern storage systems including NVMe and virtual distributed storage can produce millions of IOPS. Modern machines can have many terabytes of main memory allowing them to store the entire database or at least the active part. Also, they can include hundreds of CPU cores. Simply put, traditional assumptions are out of date and database engines need to evolve to leverage modern hardware.

The Buffer Mapping

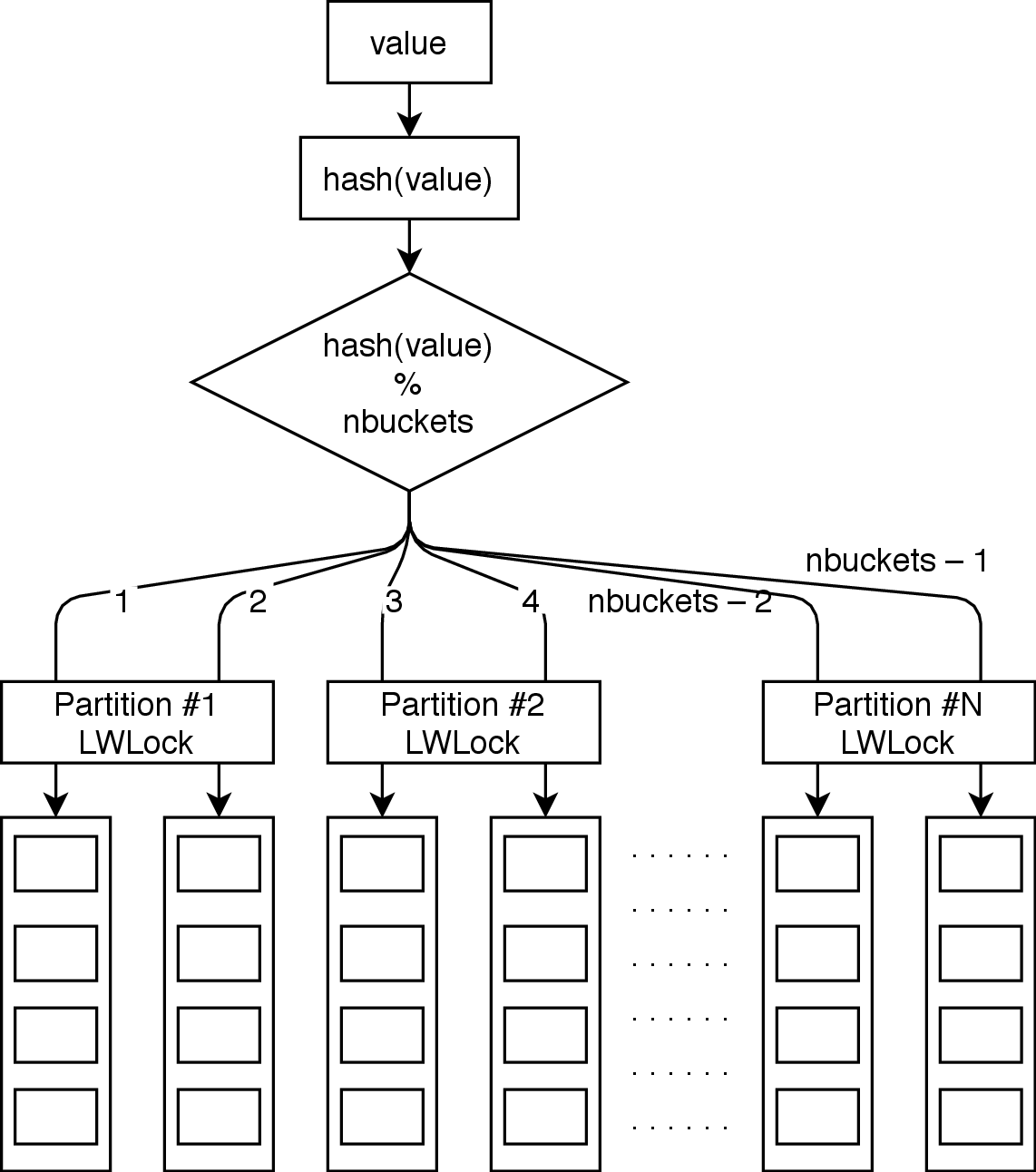

PostgreSQL currently utilizes the traditional approach to buffer management, which includes explicit buffer mapping between disk and memory. This is depicted in the figure below. The buffer mapping comprises the shared memory hash table, which allows finding an existing buffer (if any) for any disk page.

For concurrency reasons, this hash table is split into NUM_BUFFER_PARTITIONS (currently 128) partitions. Access to each partition is protected by LWLock (light weight lock).

Consider how it works for a simple operation of a single B-tree key lookup. The CPU has to access the buffer mapping hash table each time it accesses the page, even if it's a root or high-level non-leaf page.

In particular, even read-only access to the page implies the following 6 operations:

- Lock the buffer map partition,

- Pin the buffer (guarantees buffer won't be evicted),

- Unlock the buffer map partition,

- Lock the buffer content,

- Unlock the buffer content,

- Unpin the buffer.

Each of those operations implies an atomic CPU instruction. This is significant overhead. Imagine a system with hundreds of CPU cores contending for atomic operations. What could be an alternative?

In-memory databases

The huge overhead of buffer mapping gave rise to in-memory databases. In-memory databases use special data structures optimized for main memory. These data structures include skip lists, tries, special in-memory B-trees, and others. I won't get into details about these data structures since it is beyond the scope of this post. I'd like to highlight that the advantages of these data structures come at the cost of the inability to evict arbitrary pages to the storage systems. In comparison, traditional database engines have the flexibility to keep the hot part of the database in the main memory and evict the cold part to disk. I think this explains why such engines still maintain their popularity today.

Anti-caching

The idea of anti-caching 2 is to put in-memory data structure on top of on-disk data structure. Then keep only hot rows in-memory, evict least recently used rows in the on-disk data structure. Anti-caching is implemented in H-store, VoltDB and others.

Anti-caching really allows to bypass overheads of on-disk data structures for the hot data.

However, I can highlight a couple difficulties in this approach.

-

Anti-caching approach requires keeping the in-memory metadata about all the keys present in the table. Otherwise, each range query would go to the on-disk data structure. That meta-data still proportional to the whole database size.

-

Even that we have in-memory data structures, on-disk data structures still need buffering to work efficiently. So, you have to split your RAM between in-memory data and buffers.

In the same time, anti-caching provides fine-grained (row-level) in-memory caching of the data. This may help to fit more of really hot rows into RAM.

Dual pointers approach

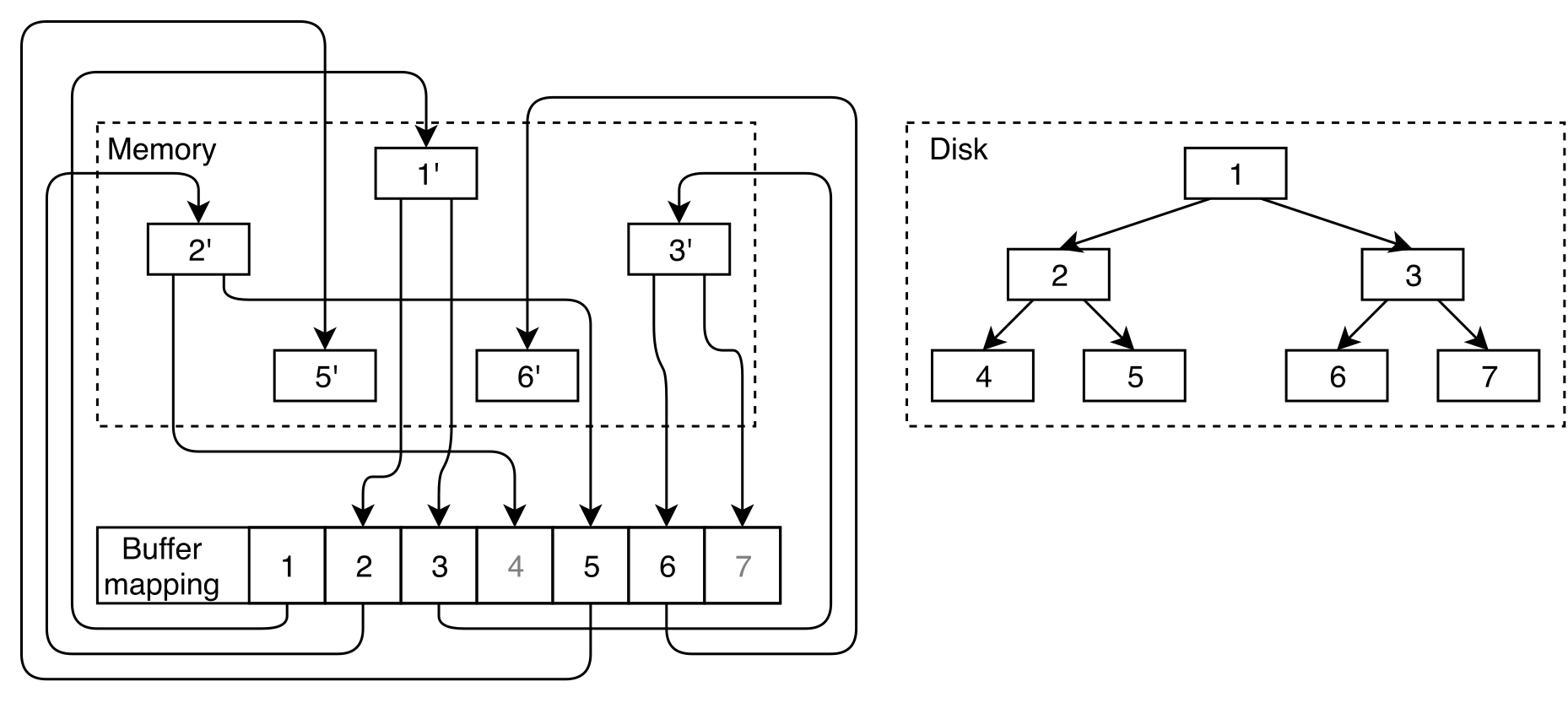

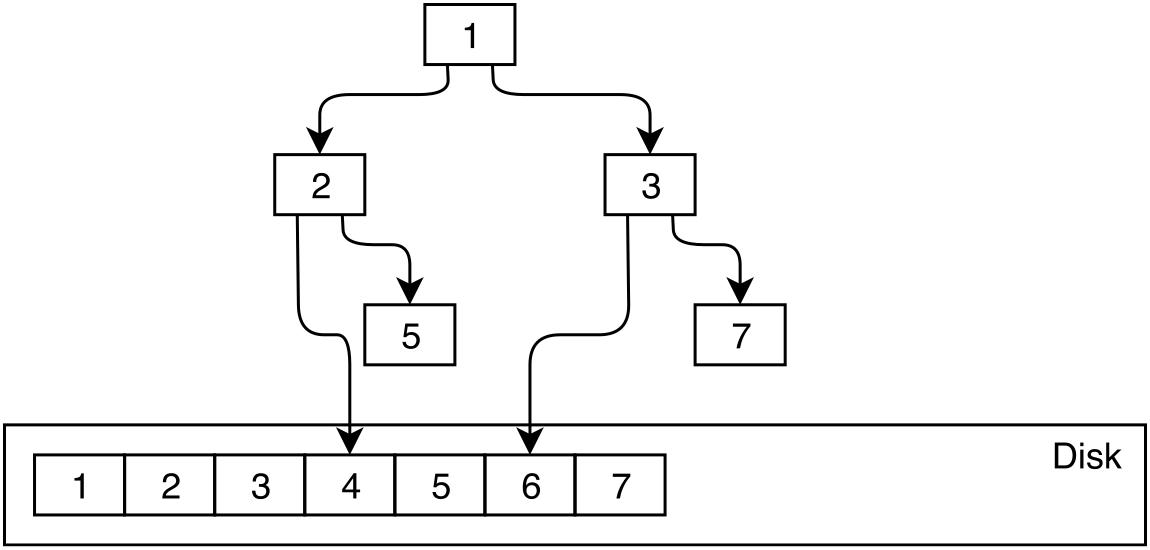

OrioleDB utilizes the dual pointer approach. The dual pointers approach means that the downlink from the in-memory page could directly refer to an in-memory or on-disk child. All in-memory pages are connected with direct links avoiding the overhead of buffer mapping.

When the on-disk child is read to memory then the parent downlink is changed accordingly. The same happens when an in-memory child is evicted from the main memory to the disk.

It seems simple. A reasonable question to ask then is "Why didn't everybody design it like this?". Actually, despite high-level simplicity, this approach requires a significant redesign of tree concurrency. See the detailed description in the docs.

| On-disk | In-memory | Anti-Caching | Dual pointers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data access layer | Buffer manager | Both in-mamory and on-disk data structures | Direct access to main memory data structures | Direct access to data pages |

| Volume restriction | Disk | RAM | Disk, but metadata should fit RAM | Disk |

Novel page structure

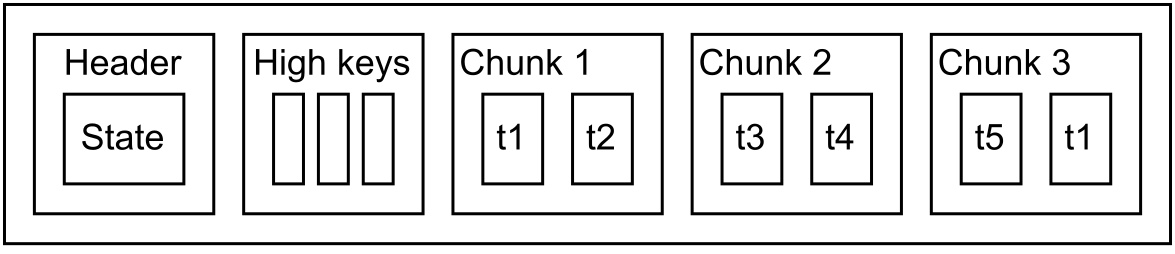

In addition to overhead related to buffer mapping, PostgreSQL has two atomic operations for every page access to lock/unlock the buffer content. This is an unpleasant consequence given that these operations need to be done even on high-level pages just for navigation purposes.

OrioleDB implements a novel page structure optimized for modern multi-core machines.

This page structure requires locking only for page modification. Reads could be done concurrently and don't involve atomic operations. See architecture documentation for details.

Benchmarks

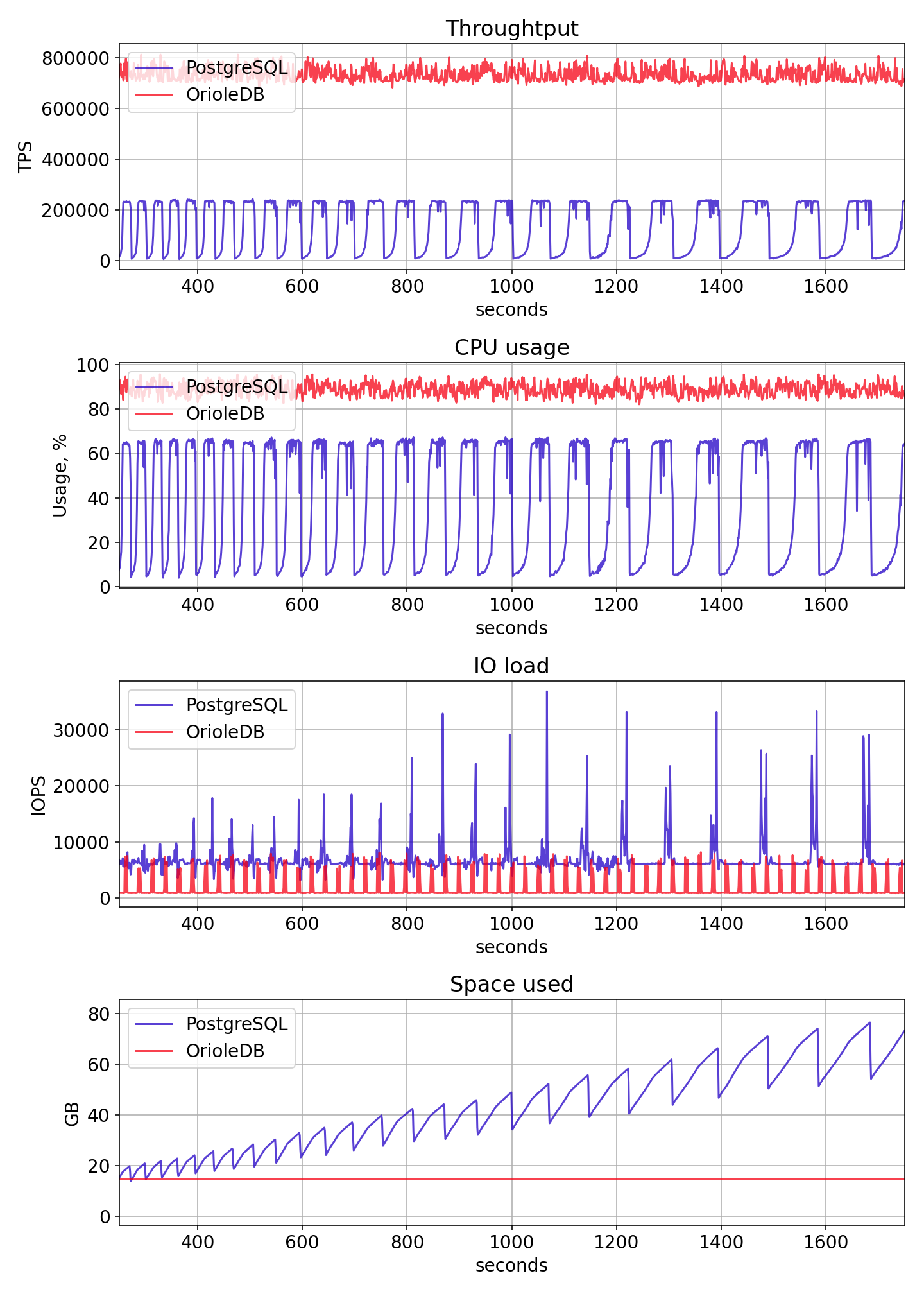

As a result of the improvements above, reading of in-memory data in OrioleDB doesn't include any atomic operations. To illustrate it let's run the read-only pgbench benchmark, which is tuned to give maximum load to the storage level, not the network. It reads 9 random values from pgbench_accounts instead of 1. The custom pgbench script is following.

\set aid1 random(1, 100000 * :scale)

....................................

\set aid9 random(1, 100000 * :scale)

SELECT abalance FROM pgbench_accounts WHERE aid IN (:aid1, :aid2,: aid3, :aid4, :aid5, :aid6, :aid7, :aid8, :aid9);

The results are given in the graph below. Thanks to the elimination of the buffer mapping bottleneck, OrioleDB is 4 times faster than the default heap engine of PostgreSQL.

Conclusion

Traditional buffer mapping was designed decades ago and, despite all of the low-level optimizations, it can't scale on modern hardware. In addition, in-memory engines limit the database size to the size of the main memory. In contrast, OrioleDB's dual pointer approach allows removing the buffer mapping overhead while saving the ability to automatically evict the least recently used pages from main memory.

PostgreSQL is an excellent DBMS, which has shown to be very scalable over decades. Nonetheless, the traditional buffer mapping design limits PostgreSQL scalability on modern hardware. Thankfully, the OrioleDB engine provides a solution within an extension and minimal patch to the core.